Returning to the U.S.

This guidance briefly reviews the relevant laws permitting border searches, describes key U.S. Customs and Border Patrol (CBP) policies relating to such searches, discusses frequently asked questions that UC faculty may have about their rights in connection with a border search, and general information about protecting sensitive data while traveling overseas on UC business.

Note: This guidance is neither offered nor intended as legal advice and is not a substitute for consultation with your Location counsel.

- Summary

- Scope of This FAQ

- What Is a “Border Search”?

- Key Questions

- The Fourth Amendment means that law enforcement needs to obtain a warrant based on probable cause to search/seize my phone/laptop at the border, correct?

- For how long can CBP seize my iPhone, laptop, thumb-drive, etc. when I return to the United States from abroad?

- Are there any limits on what CBP agents can do with my devices at the border? What is a “routine” search of my device?

- What if my device has sensitive data about research subjects, patients, or attorney-client privileged information?

- Can I be forced to disclose the password to an electronic device at the U.S. border?

- What if I refuse to give access to my devices?

- I’ve been asked for my “consent” to a search of my devices. What does this allow CBP to do?

- What can I do to protect my data before I travel internationally?

- Additional Resources

Summary

This page addresses concerns about searches of electronic devices conducted by U.S. Customs and Border Patrol (“CBP”) at the United States territorial border and any ports of entry.1

“Border searches” are conducted without a warrant and often without any suspicion of wrongdoing. These searches involve inspection of the contents and data stored on electronic devices (including laptops, smart phones, and storage devices) belonging to any person entering the United States from overseas. All persons—U.S. citizens, lawful permanent residents, and non-U.S. nationals holding visas—are subject to such searches when crossing a U.S. border or appearing at a U.S. port of entry. The search can be highly intrusive in some circumstances, including a full, forensic examination of the device. Your device may store, by default, information about your location, contacts, emails, text messages, photos, research or work-related files and data, and information about your health. You should also be aware that UC faculty members’ devices have been searched at foreign ports of departure by foreign security services, including within Europe and Asia. So, faculty members should expect devices to be searched both upon departure from overseas and upon return to a U.S. port of entry.

Scope of this Guide

This guidance briefly reviews the relevant law permitting border searches, describes key CBP policies relating to such searches, discusses frequently asked questions that UC faculty may have about their rights in connection with a border search, and general information about protecting sensitive data while traveling overseas on UC business.

This guidance is neither offered nor intended as legal advice and is not a substitute for consultation with an attorney.

As noted below, some important issues are identified here but are not resolved in this FAQ. Some remain contested in the courts (i.e., how long a faculty member traveling on a particular visa can be detained at the border is a question of immigration law that turns on the specific circumstances involved) or require technical consultation with an IT expert (i.e., how do I secure data if I am traveling to a conflict region without reliable internet access?). Accordingly, we strongly encourage you to direct specific questions to the Office of General Counsel and the contacts for IT experts identified in the attached document for detailed technical advice about securing your data or securely working with data overseas before you undertake any UC-related international travel with any device containing sensitive data.2 Also review the updated guidance from UCOP Ethics, Compliance and Audit Services (ECAS) in their April 2018 Compliance Alert newsletter (see "International Compliance" on pg 3).

What Is a “Border Search”?

Federal law authorizes CBP to “inspect, search or detain” any person or items arriving in, or departing from, the territorial United States.3 The Fourth Amendment’s usual requirements of a judicial warrant and probable cause are attenuated at the international border and ports of entry under a legal doctrine called the “border search exception.”4 Under this exception, CBP can conduct a routine search of any electronic devices possessed by travelers, including smart phones, iPads, laptops, and storage devices, without a warrant or any individual suspicion of wrongdoing.

Key Questions

-

The Fourth Amendment means that law enforcement needs to obtain a warrant based on probable cause to search/seize my phone/laptop at the border, correct?

No. Under the “border search exception” to the Fourth Amendment, CBP can search items and persons entering the country without a warrant and without probable cause or, indeed, any individual suspicion of wrongdoing.5 While the Supreme Court has not specifically addressed border searches of electronic devices, lower courts have generally upheld such searches. There may some limits on the scope of such searches, as explained below. -

For how long can CBP seize my iPhone, laptop, thumb-drive, etc. when I return to the United States from abroad?

Generally, CBP asserts the authority to “detain” a device for “brief, reasonable time” to conduct a “routine” inspection of the device.6 The detention period is not to exceed five days, absent exceptional circumstances. Per CBP policy, this includes detaining a “copy” of the device contents.7

- Are there any limits on what CBP agents can do with my devices at the border? What is a “routine” search of my device?

This issue is contested in the courts. The federal appellate court overseeing the Western U.S. and California has placed limits on more intrusive device searches, such as conducting a forensic examination of a device. Such a search is likely considered “non-routine” and requires “reasonable suspicion” of a legal violation.8 Routine searches (such as a manual, by-hand inspection of a device) do not require any individual suspicion.9

-

What if my device has sensitive data about research subjects, patients, or attorney-client privileged information?

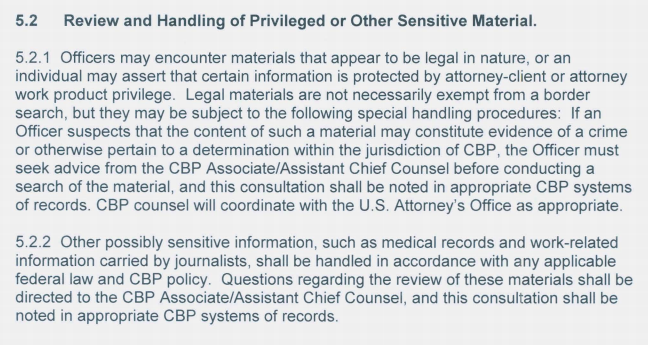

Privileged materials and medical records are not exempt from border searches. CBP policy does, however, provide special handling procedures for such records. (See Fig. 1.)CBP procedures require agents to consult with CBP legal counsel in conducting a search involving sensitive materials. If you have such materials on or accessible through your devices subject to search, you should advise CBP that you have sensitive information and potentially privileged information on the device and request that CBP follow its special handling procedures.

Fig. 1 – CBP Policy

-

Can I be forced to disclose the password to an electronic device at the U.S. border?

This likely depends on the type of password. You have a constitutional right to remain silent, and it would likely violate your constitutional rights if a government agent compelled you to verbally disclose your password to a device.10 However, some courts have concluded that the government may compel you to provide a fingerprint, or even force you to apply your own finger to a phone to unlock it.11 The distinction is that verbally providing your password is considered compulsion of your “testimony,” while the physical act of providing a fingerprint is not “testimonial” and, therefore, is not protected by the Fifth Amendment.You should assume that CBP will ask you to unlock or decrypt any device that you bring to the border and that CBP may assert authority to detain the device itself. Further, as discussed below, declining to unlock or decrypt a device may affect your entry, depending on your immigration status.

- What if I refuse to give access to my devices?

- If you are a U.S. citizen, you cannot be denied admission into the U.S. so long as you have proof of citizenship, such as your valid U.S. passport. You can be detained, however, during CBP’s inspection, and your device may be seized. Your travel may also be delayed.

- If you are a lawful permanent resident (“green card” holder), in addition to the above implications, a hearing before an immigration judge might be required in some circumstances. The implications for an individual faculty member turn on case-specific facts and circumstances; we encourage planning in advance and outreach to the Office of General Counsel for questions about specific cases.

- In general, if you are a foreign visitor or visa holder, not a lawful permanent resident, you have fewer rights at the border, and CBP can refuse to allow you to enter the country if you do not provide access to your devices. The implications for an individual faculty member turn on case-specific facts and circumstances; we encourage planning in advance and outreach to the Office of General Counsel for questions about specific cases.

-

I’ve been asked for my “consent” to a search of my devices. What does this allow CBP to do?

CBP routinely asks for your voluntary consent to search your devices. This can be as informal as asking you, “May I look at your phone please?” Opening your phone in response to a simple request may be considered consent to a search and may waive your constitutional rights. The distinction drawn above – between “routine” searches and “non-routine” searches that require some individual suspicion of wrongdoing – does not apply if you voluntarily consent in response to a request to search your devices. When you consent to a search, there is little, if any, limit to the scope of the search that the government can conduct on your devices.Accordingly, to the extent you do not wish to consent to a search, you may clarify when asked whether you are being asked to voluntarily consent to a search, or whether you are directed to open your device. In the latter case, if you do not wish to consent to the search, you may state clearly that you are opening your device only because you are being directed to do so and that you are not consenting to a search.

- What can I do to protect my data before I travel internationally?

Prepare and plan. Before you travel internationally, give careful thought to what data and devices you will need to access while in-country and what data you will acquire or generate, understanding that researchers often travel overseas for the purpose of collecting research data. You will need to plan, per below, for both accessing and securely transferring your existing data and newly-acquired data during your trip. This can be complex, as simple “cloud” access is neither simple nor ubiquitous in every country where UC faculty members conduct research.

Consult with experts at your campus/location. As noted above, your campus or school may assist you in securing data before traveling and working securely with data during your overseas trip.12 You can use a loaner device, if available, and appropriately check-in the device upon your return to ensure no malicious software was introduced during your trip. You can consult with your experts about how to securely work with sensitive data either acquired during your trip or data you will need to access during your trip to perform your work. They can advise you on tips for securely connecting to from overseas. This is not because of the possibility of disclosure to a government agent at the border, but because there are significant cybersecurity risks in connecting to the web overseas and/or having your device seized or inspected by a foreign government official.13

Data minimization. For existing data you need to access while overseas, you may consider what data you need and limit storage of any other data that you do not plan to access during your travel. For sensitive data you must access to conduct business overseas, limit on-device storage and review your options for cloud-based storage or remote access solutions to work with sensitive data without local storage.14

You have a duty to protect sensitive data. Remember that you have a duty under the law and UC policy to protect personal and confidential information relating to UC business, whether such data is stored on or accessed through a personal device or a UC-owned device. You must observe UC’s Acceptable Use policy for UC-owned devices and the Information Technology User Agreement with respect to such data.15

Encryption. Note that some countries restrict the importation of encryption software. In addition, some controlled data and technologies are restricted from being taken overseas under U.S. export control laws. Please check with your Export Control coordinator at your campus location before traveling with controlled data or encrypted software to ensure that you are aware of the import/export restrictions of every country where you will enter, even on layovers.16

Additional Resources

- http://www.ucgo.org/

- http://www.ucop.edu/ethics-compliance-audit-services/compliance/international-compliance/international-travel.html

- https://www.fbi.gov/file-repository/business-travel-brochure.pdf/view

1New York Times, “Border Officers Nearly Double Searches of Electronic Devices, U.S. Says,” April 11, 2017.

2For example, UCLA Health has a “loaner device” program that provides for on-boarding a faculty or staff member with a new device for overseas travel and assists with inspection of the loaner device upon return. See https://dgit.healthsciences.ucla.edu/pages/itconnect. In addition, the Berkeley campus has helpful guidelines and resources for securing devices and data when planning an overseas trip and, critically, tips for working securely with data while overseas. See https://security.berkeley.edu/resources/best-practices-how-articles/security-tips-international-travel.

3 8 U.S.C. § 1582; 19 C.F.R § 162.6.

4United States v. Ramsey, 431 U.S. 606, 616 (1977) (“That searches made at the border, pursuant to the longstanding right of the sovereign to protect itself by stopping and examining persons and property crossing into this country, are reasonable simply by virtue of the fact that they occur at the border, should, by now, require no extended demonstration.”).

5United States v. Ramsey, 431 U.S. 606, 616 (1977) (“That searches made at the border, pursuant to the longstanding right of the sovereign to protect itself by stopping and examining persons and property crossing into this country, are reasonable simply by virtue of the fact that they occur at the border, should, by now, require no extended demonstration.”).

6CBP Directive No. 3340-049, Border Search of Electronic Devices Containing Information, Sec. 5.3.1, “Detention and Review by CBP” (August 20, 2009).

7 Ibid.

8United States v. Cotterman, 709 F.3d 952, 967-78 (9th Cir. 2013) (“comprehensive and intrusive” forensic search of a laptop requires reasonable suspicion).

9While a recent Supreme Court decision concluded that searches of data stored remotely, such as in cloud storage accounts, have heightened Fourth Amendment protection, courts have not resolved whether this principle extends to the “border search” context. See Riley v. California, 134 S. Ct. 2473 (2014) (requiring judicial warrant based on probable cause to search contents of smart phone post-arrest).

10Doe v. United States, 487 U.S. 201, 211 (1988) (under the Fifth Amendment, the government cannot force a person to “disclose the contents of his own mind”) (quotation and citation omitted). Note that, for non-citizens and non-lawful permanent residents, refusal to provide access to a device may result in denial of entry, though this is a question of immigration law beyond the scope of this guidance.

11Schmerber v. California, 384 U.S. 757, 764 (1966) (government can compel provision of physical evidence and even performance of physical acts); United States v. Hubbell, 530 U.S. 27, 34-35 (2000) (“[E]ven though the act may provide incriminating evidence, a criminal suspect may be compelled to put on a shirt, to provide a blood sample or handwriting exemplar, or to make a recording of his voice.”); see also Virginia v. Baust, No. CR14-1439, 2014 WL 6709960, at *3 (Va. Cir. Ct. Oct. 28, 2014) (forcing murder suspect to produce fingerprint to unlock his iPhone to seek video evidence of crime).

12See above, footnote 3.

13See “Passport and Travel Information – Country Information - China,” U.S. Department of State, Bureau of Consular Affairs, available at https://travel.state.gov/content/passports/en/country/china.html (accessed on May 2, 2017) (warning U.S. travelers that “[s]ecurity personnel carefully watch foreign visitors and may place you under surveillance …. telephones, Internet usage, and fax machines may be monitored onsite or remotely, and personal possessions in hotel rooms, including computers, may be searched without your consent or knowledge. Security personnel have been known to detain and deport U.S. citizens sending private electronic messages critical of the Chinese government.”).

14We are aware of concerns that IRB-approved research protocols may restrict the use of cloud-based storage, though most IRBs do not do so. Please review any IRB protocols governing security of your research data and, if needed, consult with the Office of General Counsel or your Office of Research.

15See “Safety and Security for U.S. Students Traveling Abroad,” Federal Bureau of Investigation, available at https://www.fbi.gov/file-repository/student-travel-brochure-pdf.pdf/view (accessed on May 2, 2017) (noting that you should assume that all internet and phone communications are being intercepted and recommending that you “sanitize” electronic devices of sensitive “contact, research or personal data”).

16For more information, see the UCOP Office of Ethics, Compliance and Audit Services’ website for information on export control at http://www.ucop.edu/ethics-compliance-audit-services/compliance/international-compliance/international-travel.html